邱仁宗、雷瑞鹏域外撰文介绍中国防疫工作及其伦理问题

摘要: 应对新型冠状病毒疫情中的伦理问题(英文版) Report from China: Ethical Questions on the Response to the Coronavirus By Ruipeng Lei and Renzong Qiu Hegel says,...

【编者按】

新型冠状病毒肺炎疫情的蔓延,牵动着全世界人民的心。日前,著名生命伦理学家、中国人民大学伦理学与道德建设研究中心研究员兼生命伦理学研究所所长邱仁宗,华中科技大学哲学系教授兼生命伦理研究中心执行主任雷瑞鹏,在世界上第一个生命伦理学研究中心——黑斯廷斯中心官方网站撰文,向世界介绍中国政府和人民防控新型冠状病毒肺炎疫情的最新进展和巨大努力,并提出一些值得关注的伦理问题。我们看到,疫情防控正在向好的方向发展,邱仁宗研究员、雷瑞鹏教授提到的一些伦理问题,也引起了人们和政府的重视。今天,我们将文章翻译出来,供广大伦理学人研究学习参考。

邱仁宗,黑斯廷斯中心研究员(Fellow)中国人民大学伦理学与道德建设研究中心研究员兼生命伦理学所所长

雷瑞鹏,黑斯廷斯中心研究员(Fellow)华中科技大学哲学系教授兼生命伦理学研究中心执行主任

黑格尔说,“我们从历史当中学到的教训是,我们不会从历史中吸取教训”。冠状病毒疫情在中国重新出现,证明了他的深刻见解是对的。

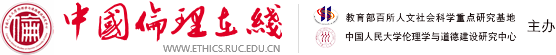

16年前,SARS大流行曾在中国大陆猖獗一时,并跨越国境,引起了全球的灾难。如今的病原体则是SARS病毒的亲戚——一种新的冠状病毒(名称为2019 n-CoV)。截至北京时间1月31日,中国国家卫健委的数据显示已有9720人确诊感染新型冠状病毒,并有15238人疑似感染;213人死亡,175人被治愈。患病者中一大部分都来自湖北省。由于中国以外的国家和地区确诊人数不断增加,世界卫生组织(WHO)在1月30日宣布,新型冠状病毒疫情为国际关注的突发公共卫生事件。

审视这场新型冠状病毒疫情,其中有不少的科学问题,包括病毒是否来自武汉市华南海鲜市场、还是其他地方。然而,在应对冠状病毒疫情的过程中,一些伦理问题也需要关注。

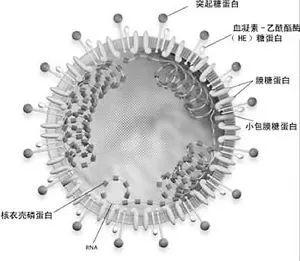

让我们从中央电视台的专访中开始说起。主持人向中国疾控中心副主任冯子健提出了一个问题:第一例新型冠状病毒的感染者在2019年12月8日被上报,确诊感染病例用了超过40天才达到500例;2020年1月22日,全国确诊病例为571例,仅仅过了两天,这个数字就达到1000例。到1月27日确诊病例超过了2800。主持人问道,您认为是什么导致了确诊病例的快速增加?这有什么含义?——这也是一个绝大多数中国人希望得到答案的一个问题。

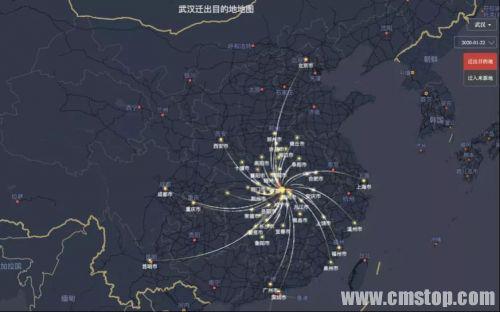

冯子健医生表示,新病毒的传播能力比SARS更强。他将新型冠状病毒的快速扩散归因于春节假期(1月25日-2月2日),在此期间,中国的交通出行人数预计多达30亿人次。这些出行的人员可能接触和传播病毒。然而,我们认为,新型冠状病毒感染人数的遽然上升另有原因,正是这些原因导致了1月17日前确诊人数的数据呈平稳状态,但此后快速上升。

【缺乏信息透明性】

在控制疫情的努力之中,信息的透明性至关重要,非此,不足以让公众了解如何保护自己,也不足以让医疗和公共卫生专业人员知晓应该采取何种有效而适宜的干预措施。现在,中国国家卫健委已经每天都会更新疫情的最新数据;北京和各大城市都会及时举行记者会发布疫情简报,公布疫情扩散信息,并在电视上与疫情专家进行访谈——这样的措施满足了疫情透明的伦理原则。然而,1月28日,中国在线杂志《第一财经》发表了一篇题为《1月6日之后,12天病例零新增之谜》的特别报道,指出从1月11日到1月16日间,武汉市报告的新型冠状病毒感染病例维持在41人不变,长达6天。在这期间没有新病例引起了人们的怀疑:关于疫情的实际消息被掩盖了,导致公众被误导,错失控制病毒传播的黄金时间。

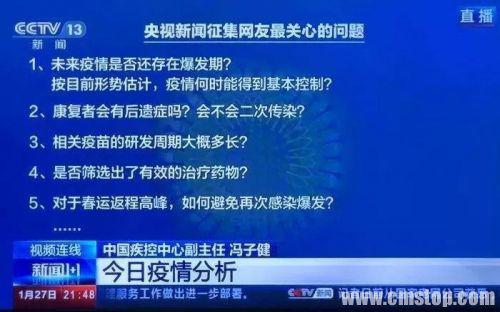

作者报道说,在此期间于武汉举办了“两会”——1月7日至10日的省人大会议,与1月11日至17日的省政协会议。“两会”期间是歌功颂德的时候,不去对付麻烦问题,不提可能的失误。2019年的最后一天,《湖北日报》为全省2019年的发展成果做了12个整版的特别报道,仅在最后一版的右下角,发表了一小段武汉市卫健委通报的肺炎疫情信息。在这个期间,疫情的信息并不是每日报道的,而从1月6日至1月9日则完全没有报道。武汉卫健委发布的通报,一直在强调以下几点:所有患者均在武汉市医疗机构接受隔离治疗;未发现明确的人传人证据;未发现医务人员感染。到了1月21日至23日,湖北省和武汉市政府甚至还组织了规模不小的团拜会和文艺演出会,以庆祝春节的到来,出席的有湖北省和武汉市的许多领导人。这些活动向公众传达了一个起误导作用的信息,让他们以为疫情并非一个严重问题。

对于疫情更新的忽视以及发布虚构和误导的信息,不仅转移了公众的注意力,更影响了医疗和公共卫生人员对疫情控制的努力。这是政治考虑严重地损害公共卫生干预的一例。湖北省和武汉市的行为,已经违反了我国《传染病防治法》第37条——依照本法的规定负有传染病疫情报告职责的人民政府有关部门、疾病预防控制机构、医疗机构、采供血机构及其工作人员,不得隐瞒、谎报、缓报传染病疫情。因此,湖北省和武汉市的官员应该对此负有法律责任。

【关于隔离和检疫】

在一场缺乏特效药和疫苗的疫病大流行疫情当中,隔离和检疫是唯一有效的干预措施。中国采取了多种隔离和检疫措施:

•社区防控:其措施包括公众聚会,以减少人与人的接触并尽早发现受感染的病人。

•14天自我隔离:要求在武汉或湖北省工作的人居家隔离14天,除购买生活必需品外不得外出。而在购买必需品时,他们则要佩戴口罩。

•隔离治疗:新型冠状病毒的确诊和疑似病例应在定点医院进行隔离和治疗。

•封锁城市:包括武汉在内的湖北各城市被封锁即检疫,居民不得前往中国的其他地方。

中国的传染病法律授权政府可以通过封锁严重疫区控制疫情,即检疫。但封锁城市这一决定在伦理学上是否能得到辩护,是有争议的。在我们看来,如果封锁城市能够满足以下要求,它就可以被认为能够在伦理学上得到辩护:

第一,这一干预措施能够有效控制疫情;

第二,它与疫情的严重程度是相称的;

第三,它对控制疫情必不可缺;

第四,它对个人自由和权利仅有最低程度的侵犯;

第五,它对公众是公开透明的。

大致上说,封锁武汉及其他城市大致符合这些条件。在武汉封城之前,居住在那里的500万人在外旅行;在中国其他地区发现的确诊和疑似病例中,大部分曾到过武汉或曾与来自武汉者接触过的人。从这个意义上说,封锁武汉可以延缓病毒的传播速度。

【有待解决的伦理问题】

中国政府采取的一些措施,对于控制疫情有着正面影响。中国政府宣布,所有新型冠状病毒肺炎确诊感染者的医药费(无论住院还是门诊)都将由政府承担,疑似病例的门诊费用也将由政府一并承担。春节假期被延长三天,各大学校的开学时间则被规定不早于2月17日,这样的举措有助于控制交通流量,减少病毒传播。中央政府还出台法律,禁止在疫情结束前一切形式的野生动物交易。不过,仍有若干伦理问题需要得到解决。

我们从SARS疫情的教训中了解到,食用野生动物可能会导致病毒在人群中扩散。既然如此,为何我们还要继续允许市场和餐馆出售野味?为了避免未来疫情重演,我们是否应该改变传统的文化习惯?野生动物交易的临时性禁令是否应该是永久的?早在2019年11月,已经检出一些武汉的病人患有不明肺炎。为何当地卫生部门官员没有将这些病例上报给疾控中心,并设法从这些病人的生物学样本中分离出病原体并鉴定其性质?为什么在疫情出现的初期,武汉卫健委将疫情描述为“可防可控”、“没有明显的人传人证据”?

中国公众和国际社会得到的疫情信息是足够的吗?是完整的吗?是可靠的吗?如何证明没有出现隐瞒不报?

中国各地已经实施的隔离和检疫措施,都是能够在伦理学上得到辩护,并且是与疫情严重程度相称的吗?这些干预措施是否将对个人自由和权利的侵犯限制到了最低程度?

隔离治疗无可避免的会导致药品、设备和医护人员的缺少。我们如何保证这些资源的公平可及和公正的分配?

我们是否应该采取措施有效地阻止和反对对来自武汉或感染病毒的人的歧视?

医务工作者有治疗新型冠状病毒感染者的道德义务吗?医疗卫生管理部门和政府有为坚守岗位的医务工作者提供额外支持的道德责任吗?

我们希望中国能够从当下这次冠状病毒大流行中汲取教训,改革政策和法律,以改善信息的透明性,保证疫情的准确性和及时更新,并解决这次大流行提出的许多伦理问题,以证明黑格尔说得并不完全正确:我们在付出了极其巨大而惨痛的代价后,能够从历史当中学到一些东西。

应对新型冠状病毒疫情中的伦理问题(英文版)

Report from China: Ethical Questions on the Response to the Coronavirus

By Ruipeng Lei and Renzong Qiu

Hegel says, “We learn from history that we do not learn from history.” The recurrence of the coronavirus epidemic in China proves his insight to be right.

Sixteen years ago, the SARS pandemic was ravaging mainland China and spreading beyond the border to cause global catastrophe. Now we have a SARS cousin, the novel coronavirus (2019 n-Cov). As of January 31, according to the National Health Commission, there were 9,720 confirmed cases and 15,238 suspected cases in China; 213 people have died, and 175 have recovered. The majority of the cases are in Hubei Province. On January 30, the WHO (World Health Organization) decided that the epidemic of 2019 n-Cov is a public health emergency of international concern, based on the increase of confirmed cases in the countries and regions outside China. There are many scientific questions, including whether the virus came from the South China Seafood Market in Wuhan or elsewhere. And there are ethical questions about the response to the spreading virus.

In an interview on CCTV with Dr. Feng Zijian, the deputy director of China’s Centers for Disease Control, the anchorman asked a question that all Chinese people want the answer to: what is causing the rapid increase in confirmed cases? The first case was reported on December 8, 2019, and it took more than 40 days to surpass the 500th case; there were 571 cases on January 22. Just two days later, there were 1,000 cases. By January 27 there were more than 2,800 confirmed cases. The news anchor asked, “What do you think of the rapid change in the data? What does it mean?” Dr. Feng said that the transmission capacity of the new virus is stronger than that of SARS. He attributed the rapid spread of the virus during this period to the Spring Festival (January 25-February 2), when as many as 3 billion people travel and can be exposed to, and transmit, the virus. However, we argue that other factors made the growth in cases plateau before January 17 and rise sharply afterward. Lack of Transparency In the efforts to control the epidemic, transparency is a key principle to let citizens know how to protect themselves and to let medical and public health personnel know which effective and appropriate interventions should be taken. Now, the National Health Commission updates data on the epidemic every day. There are timely briefings at press conferences in Beijing and other cities to report the updated information on the spread of the virus and interviews with epidemic experts on TV. It is good that the ethical principle of transparency is being followed now. However, there was a lack of transparency earlier in January. On January 28, a special report titled “The Puzzle of No New Case for 12 Days after 6 January,” published in the online journal YiMagazine, said that, strangely enough, from January 11 to 16, the number of confirmed cases in Wuhan remained unchanged at 41. The lack of reported new cases raised the suspicion that true information was being hidden, and that the public was misled and missed the opportunity to control the spread of the virus. The author reported that two meetings were held in Wuhan: the Hubei Provincial People’s Congress on January 7 to 10 and the Political Consultation Conference on January 11 to 17. This is the time to sing the praise of the government’s achievement, not to deal with problems and expose mistakes. Hubei Daily published a special report with 12 pages to praise the province’s achievement. In the lower corner of the last page, there was information on the epidemic issued by the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission. During this period, information on the epidemic was not reported every day, and there was no report from January 6 to January 9. The Wuhan Health Commission’s notifications made only the following points: All patients were receiving isolation treatment in medical institutions, no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission was found, and no medical staff members were infected. On January 21 and 23, Hubei provincial and Wuhan municipal authorities organized largescale gatherings and artist performances to celebrate the Spring Festival, with the presence of the leaders of Hubei Province and city of Wuhan These activities conveyed a misleading message to the public that the epidemic was not a serious problem. The omission of updates on the epidemic and faked, misleading information shifted the public’s attention from the epidemic and inhibited the efforts by medical and public health staff to control it. This is a case in which public health intervention was devastatingly compromised by the politics. It violated Article 37 of the Law on Infectious Diseases, which stipulates that the relevant departments of the people’s government shall not conceal, make false reports, or delay the report of the epidemic situation of infectious diseases. The provincial officials should be legally liable. Isolation and Quarantine In an epidemic without effective drugs or a vaccine, isolation and quarantine may be the only effective interventions. There are various forms of isolation and quarantine in China: · Community prevention and control: measures include prohibiting public gatherings to reduce personal contacts and detect infected patients as early as possible.· Self-quarantine for 14 days: people who work in Wuhan or throughout Hubei Province are required to stay home for 14 days without going out in public except for essential shopping; they must wear face masks when shopping.· Isolation treatment: suspected and confirmed cases should be isolated and treated in designated hospitals.· Quarantining cities: Wuhan and other cities in Hubei Province are quarantined, meaning that the residents cannot go to other places in China. Under China’s Law on Infectious Diseases, the government can seal off, or quarantine, the serious epidemic area. What is controversial is whether the decision is ethically justified. In our opinion, it is ethically justified if it is effective in controlling the epidemic, it is proportional to the severity of the epidemic, it is necessary for controlling the epidemic, it is taken with minimal infringement on individual freedom and rights, and it is transparent to the public. Sealing off Wuhan and other cities roughly meets these conditions. Before Wuhan was sealed off, 5 million people living there traveled outside the city. The largest number of confirmed and suspected cases in all other areas of China are people who had traveled to Wuhan or were in contact with people from Wuhan. Sealing off Wuhan may reduce the spread of the virus. Ethical Issues to Be Addressed Some decisions made by the government have been beneficial to controlling the epidemic: All medical (inpatient and outpatient) costs for confirmed cases and for outpatient services to suspected cases are covered by the government; the Spring Festival will be prolonged by three days, and the start of the spring semester for school will be no earlier than February 17 to reduce the flow of travel and the spread of the virus; and the central government banned all forms of trade in wild animals until the end of the epidemic. But there are several ethical issues that need to be addressed. We knew from the SARS epidemic that using wild animals for food may promote the spread of the virus to people. Why did we continue permitting markets and restaurants to provide food from wild animals? Should we change traditional cultural customs to prevent future epidemics? Should the temporary ban on wild animal trade be permanent? As early as November 2019, some patients in Wuhan were detected with an unidentified pneumonia-like illness. Why didn’t the local health officials report these cases to the central center for disease control and try to isolate the pathogen from the biological samples of these patients and identify its nature? Why, at the beginning of the epidemic, did the Wuhan Health Commission characterize the infection as mild, treatable, and under control? Why did the commission say, without adequate supporting evidence, that there was no transmission from human to human? Was the information about the epidemic disclosed to the Chinese public and international community adequate, complete, and faithful, without any cover-up? Are the cases of isolation and quarantine that are in effect ethically justifiable and proportionate? Do these interventions minimize the infringement upon individual freedom? Isolation treatment unavoidably leads to the shortage of drugs, equipment, and medical staff. How do we ensure equitable access to and fair allocation of these resources? Which interventions should we take to effectively prevent and fight discrimination against the people from Wuhan or those infected with the virus? Do medical staff have a moral responsibility to treat patients infected with the virus? Do health administrative departments and the government have a responsibility to provide extra support to medical staff who stick to their posts? We hope China can learn from the latest coronavirus epidemic and reform policy and law to improve transparency, require accurate and timely updates, and address the many ethical questions that an epidemic raises to prove that what Hegel says is not all correct: We can learn a little bit from history after paying extraordinarily great and painful costs. Ruipeng Lei, a Hastings Center Fellow, is Professor and Executive Director Center for Bioethics Huazhong University of Science & Technology. Renzong Qiu, a Hastings Center Fellow, is Professor and Director, Institute of Bioethics, Center for Ethics & Moral Studies, Renmin University of China.

图片源于人民网等

责任编辑:张伟东

There are many scientific questions, including whether the virus came from the South China Seafood Market in Wuhan or elsewhere. And there are ethical questions about the response to the spreading virus.

In an interview on CCTV with Dr. Feng Zijian, the deputy director of China’s Centers for Disease Control, the anchorman asked a question that all Chinese people want the answer to: what is causing the rapid increase in confirmed cases? The first case was reported on December 8, 2019, and it took more than 40 days to surpass the 500th case; there were 571 cases on January 22. Just two days later, there were 1,000 cases. By January 27 there were more than 2,800 confirmed cases. The news anchor asked, “What do you think of the rapid change in the data? What does it mean?” Dr. Feng said that the transmission capacity of the new virus is stronger than that of SARS. He attributed the rapid spread of the virus during this period to the Spring Festival (January 25-February 2), when as many as 3 billion people travel and can be exposed to, and transmit, the virus. However, we argue that other factors made the growth in cases plateau before January 17 and rise sharply afterward. Lack of Transparency In the efforts to control the epidemic, transparency is a key principle to let citizens know how to protect themselves and to let medical and public health personnel know which effective and appropriate interventions should be taken. Now, the National Health Commission updates data on the epidemic every day. There are timely briefings at press conferences in Beijing and other cities to report the updated information on the spread of the virus and interviews with epidemic experts on TV. It is good that the ethical principle of transparency is being followed now. However, there was a lack of transparency earlier in January. On January 28, a special report titled “The Puzzle of No New Case for 12 Days after 6 January,” published in the online journal YiMagazine, said that, strangely enough, from January 11 to 16, the number of confirmed cases in Wuhan remained unchanged at 41. The lack of reported new cases raised the suspicion that true information was being hidden, and that the public was misled and missed the opportunity to control the spread of the virus. The author reported that two meetings were held in Wuhan: the Hubei Provincial People’s Congress on January 7 to 10 and the Political Consultation Conference on January 11 to 17. This is the time to sing the praise of the government’s achievement, not to deal with problems and expose mistakes. Hubei Daily published a special report with 12 pages to praise the province’s achievement. In the lower corner of the last page, there was information on the epidemic issued by the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission. During this period, information on the epidemic was not reported every day, and there was no report from January 6 to January 9. The Wuhan Health Commission’s notifications made only the following points: All patients were receiving isolation treatment in medical institutions, no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission was found, and no medical staff members were infected. On January 21 and 23, Hubei provincial and Wuhan municipal authorities organized largescale gatherings and artist performances to celebrate the Spring Festival, with the presence of the leaders of Hubei Province and city of Wuhan These activities conveyed a misleading message to the public that the epidemic was not a serious problem. The omission of updates on the epidemic and faked, misleading information shifted the public’s attention from the epidemic and inhibited the efforts by medical and public health staff to control it. This is a case in which public health intervention was devastatingly compromised by the politics. It violated Article 37 of the Law on Infectious Diseases, which stipulates that the relevant departments of the people’s government shall not conceal, make false reports, or delay the report of the epidemic situation of infectious diseases. The provincial officials should be legally liable. Isolation and Quarantine In an epidemic without effective drugs or a vaccine, isolation and quarantine may be the only effective interventions. There are various forms of isolation and quarantine in China: · Community prevention and control: measures include prohibiting public gatherings to reduce personal contacts and detect infected patients as early as possible.· Self-quarantine for 14 days: people who work in Wuhan or throughout Hubei Province are required to stay home for 14 days without going out in public except for essential shopping; they must wear face masks when shopping.· Isolation treatment: suspected and confirmed cases should be isolated and treated in designated hospitals.· Quarantining cities: Wuhan and other cities in Hubei Province are quarantined, meaning that the residents cannot go to other places in China. Under China’s Law on Infectious Diseases, the government can seal off, or quarantine, the serious epidemic area. What is controversial is whether the decision is ethically justified. In our opinion, it is ethically justified if it is effective in controlling the epidemic, it is proportional to the severity of the epidemic, it is necessary for controlling the epidemic, it is taken with minimal infringement on individual freedom and rights, and it is transparent to the public. Sealing off Wuhan and other cities roughly meets these conditions. Before Wuhan was sealed off, 5 million people living there traveled outside the city. The largest number of confirmed and suspected cases in all other areas of China are people who had traveled to Wuhan or were in contact with people from Wuhan. Sealing off Wuhan may reduce the spread of the virus. Ethical Issues to Be Addressed Some decisions made by the government have been beneficial to controlling the epidemic: All medical (inpatient and outpatient) costs for confirmed cases and for outpatient services to suspected cases are covered by the government; the Spring Festival will be prolonged by three days, and the start of the spring semester for school will be no earlier than February 17 to reduce the flow of travel and the spread of the virus; and the central government banned all forms of trade in wild animals until the end of the epidemic. But there are several ethical issues that need to be addressed. We knew from the SARS epidemic that using wild animals for food may promote the spread of the virus to people. Why did we continue permitting markets and restaurants to provide food from wild animals? Should we change traditional cultural customs to prevent future epidemics? Should the temporary ban on wild animal trade be permanent? As early as November 2019, some patients in Wuhan were detected with an unidentified pneumonia-like illness. Why didn’t the local health officials report these cases to the central center for disease control and try to isolate the pathogen from the biological samples of these patients and identify its nature? Why, at the beginning of the epidemic, did the Wuhan Health Commission characterize the infection as mild, treatable, and under control? Why did the commission say, without adequate supporting evidence, that there was no transmission from human to human? Was the information about the epidemic disclosed to the Chinese public and international community adequate, complete, and faithful, without any cover-up? Are the cases of isolation and quarantine that are in effect ethically justifiable and proportionate? Do these interventions minimize the infringement upon individual freedom? Isolation treatment unavoidably leads to the shortage of drugs, equipment, and medical staff. How do we ensure equitable access to and fair allocation of these resources? Which interventions should we take to effectively prevent and fight discrimination against the people from Wuhan or those infected with the virus? Do medical staff have a moral responsibility to treat patients infected with the virus? Do health administrative departments and the government have a responsibility to provide extra support to medical staff who stick to their posts? We hope China can learn from the latest coronavirus epidemic and reform policy and law to improve transparency, require accurate and timely updates, and address the many ethical questions that an epidemic raises to prove that what Hegel says is not all correct: We can learn a little bit from history after paying extraordinarily great and painful costs. Ruipeng Lei, a Hastings Center Fellow, is Professor and Executive Director Center for Bioethics Huazhong University of Science & Technology. Renzong Qiu, a Hastings Center Fellow, is Professor and Director, Institute of Bioethics, Center for Ethics & Moral Studies, Renmin University of China.

责任编辑: